A practice of Lord Ixtlilton

Introductory remark: this article describes a shamanic/spiritual practice to “download” the “spirit” of a “deity” through drawing it. Hereafter I will explain the process using the Nahuatl language of the Nahua people (which includes the Toltecs, “Aztecs” or Mexica, etc.)

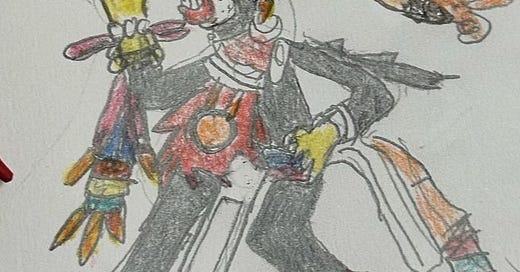

In the Tonalpohualli, Ixtlilton appears in the plate number 62 of the Borgia Codex as part of the trecena Ce Kuauhtli (1 Eagle). An important way to absorb the “energy” of this teteotl is by drawing it. In the Nahuatl language “drawing/writing” is said “ihkwilowa” — the root “ih” refers to “breath”, in particular to one of the three types of “souls” or “spirit” that humans have: Ihiyotl, this spirit (wind, soul) that leaves the body and goes to Mictlán after we die; “kwi” means “to take”; “wa” means “to register”: therefore “ihkwilowa” is a way to “download a soul” that exists in the numinous by taking it down in the concrete: this world of coarse matter, the world of cognition and sensory bases. So by drawing Ixtlilton, using the symbology of the Tonalpohualli, the tlacuilo or painter is bringing the energy of this deity into their own body — try it!

Ixtlilton is “the little one of the black face”, he is related to Yayauhtik Tezcatlipoca (Black Tezcatlipoca). He is associated with dancing, Ixtlitlon is the dancer, “the Earth stomper” (Tlaltetecuini). His body is painted in color black, with red paint around his mouth. Notice his necklace pendant as well, it is Huehuecoyotl’s (the Old Coyote) pointed oval pectoral. He performs several functions and is related to medicine, in particular children’s medicine. When a child was sick, their parents would take them to Ixtlilton’s temple, called Tlacuilocan, were a medicine or remedy was prepared. Among those remedies related to Ixtlilton was a drink called “tlilatl” – we don’t know what that medicine contained but it was a “black water”. It is related to pulque somehow — perhaps a sort of soft pulque with aguamiel and other plants and herbs.

This drink tlilatl was also related to #tlacuilo (painter scribes), so again another reason for a practice of Ixtlilton. It was said that tlilatl was “ink”. So there was a relationship between ink and what children would drink as medicines in these cases. Finally, In “Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate” (2007) Hill Bone tells us that Ixtlilton “as a healer and diviner, his bowl of black water healed children and revealed adulterers and thieves”.

May Update: it was brought to my attention that in “The masked language” (Mikulska, 2008) the author examines the nature of oral language and graphical representations, in particular Nahuatl, and refers to “icuiloa” —although she doesn’t use the same grapheme as myself in this text as “ihkwilowa”, the reader must note that we’re talking about the same thing, and in that sense my own breakdown of the word offers further detail and analysis. Aside from standardization efforts, I write “ihkwilowa” because the “H” letter is meant to convey in the reader a glottal stop, a feature of spoken language that doesn’t really exist in English. But we’re talking about the same thing —the basic Nahuatl verb for “to write” or “to draw”, in particular its relation with “ih”: Soul, Spirit, that which leaves the body when we die. One thing I would bring from her own approach (page 43) is the relationship between “icuiloa” and its derivative noun “tlacuilli”, which I think I didn’t point out too well in my original article. In “tlacuilli" obviously “tla” means “person”, then the discussed “icui”/”ihkwi”, and the noun-making particle “-li”: that leaves us with a literal translation of tlacuilli or tlacuilo that means “person that does ihkwi” or more conceptually “person that records, person that takes down from Spirit”.

Matlaktli wan ome osomatli, 1 Xochitl.

May 8 2023.